…play with a steady tempo

We’ve all experienced it at least once, either on our own or playing with a group: The tempo takes on a life of its own, gradually speeding up or slowing down–or some of both! Why?

Tempo fluctuation in part come from the player’s internal perception of the tune and its pulse, and just plain paying attention. The other part, for those of us who play highly physical instruments, is this:

The movement distance of the arm(s) between strums, strikes, pinches and plucks

needs to match the tempo being played.

When the movement distance shortens, the tempo goes faster;

when the movement distance lengthens, the tempo slows down.

And when movement stops, the tempo may slow down or feel erratic, while sounding choppy.

Got that? So how one’s arm(s) move–or don’t!–is often but not completely the culprit behind a tempo problem.

If you’re a strummer, keep reading. If you’re a hammerer or string picker, click here to jump to that section.

Strumming

Here are some things you can try to play with a rock-solid tempo. You’ll have to do a little troubleshooting first, but that’s okay if you really want to know the cause. Read the whole list first to see if something in particular resonates with you.

- Be sure you know the tune or song well enough. Maybe you just need to spend more time with it? This is a good time to ensure that all the intended notes are in fact present, and that the rhythm is being interpreted accurately. It can be handy to have some music notation available; even if you don’t read, you can still see ups, downs and spaces in between notes.

- Strum for about a minute (or longer if you like) and watch your strumming arm in a mirror. Does the strum length you begin with shorten or lengthen the longer you play?

- Where does your strumming originate? At the thumb, wrist, elbow or shoulder? Find out now!

If the thumb: We are told to strum with the thumb, and while this is true in part, note that the thumb does not flex! When the thumb moves back and forth, it becomes one tired puppy. Also, the strum arc from the thumb is very small and may become smaller as the thumb tires, speeding up the tempo.

If the wrist: You’ll use a larger strum length than what the thumb gives, but it is still quite small. And like the thumb, strum length may shorten as the tune or song continues because it’s tiring, and so the tempo will increase

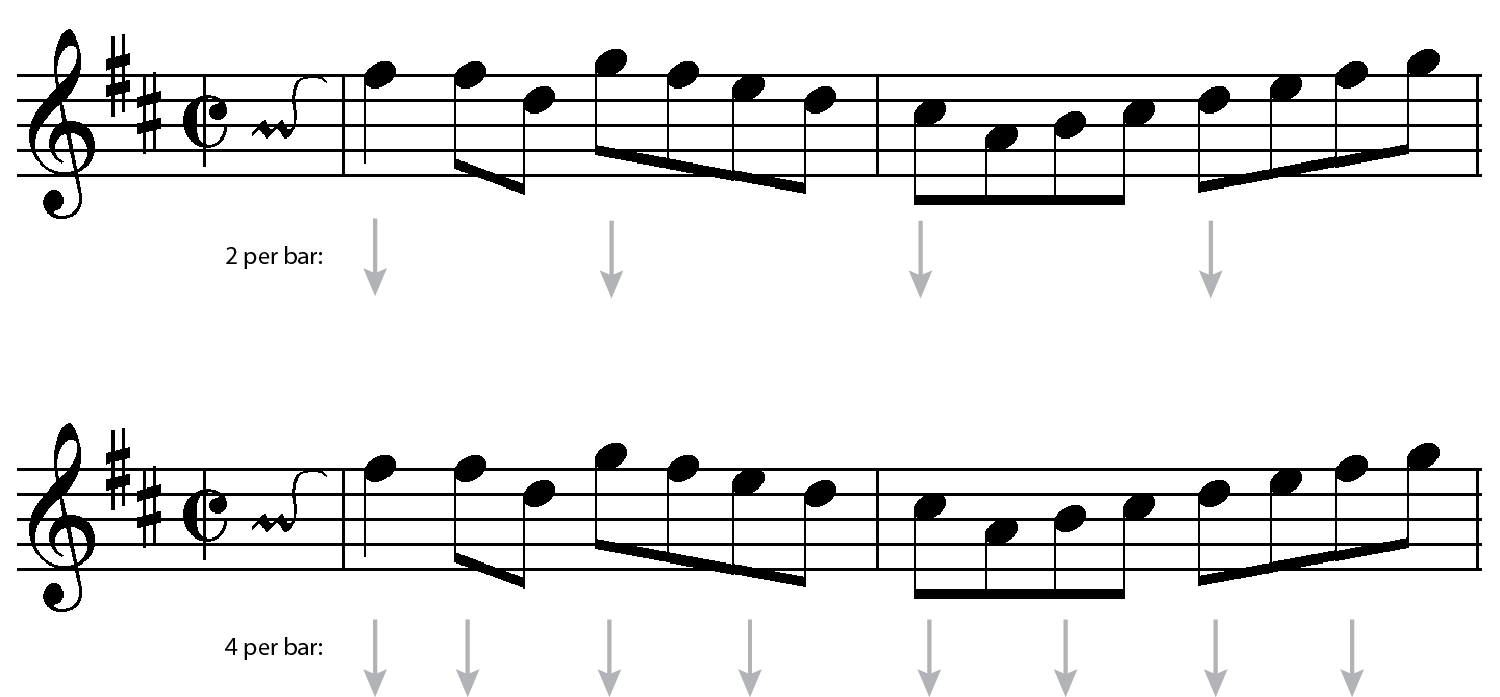

If the arm: Just from the elbow? Or do you see a little rotation responding to the elbow in the shoulder joint. This is part of what we are after. - Does the strumming direction match downbeats and upbeats in the rhythm of the moment? If not, it’s easy to speed up. Compare the strum directions in these two rhythms:

On both top staves, strumming corresponds to the rhythm, with dotted arrows showing “silent” places where the arm moves but the pick doesn’t strum. In these cases, constantly moving the arm down-up-down-up is the key, with some arm moves making no sound at all.Each bottom example also strums down-up-down-up, but the arm moves only when sound occurs, stopping within the rhythm’s “silent” spaces. Strumming this way often compromises the player’s sense of timing, leaving the tempo vulnerable to change. It also makes strumming feel rickety and “hard.” - If your strumming follows steady down-up arm moves as per each top example above, then shortening the strum length may come from the playing hand avoiding contact with your other arm (autoharp), your lap (guitar) or your torso (mountain dulcimer). Go ahead and let your strumming hand “bump into” whatever the body part is (gently with a “bounce”) and listen to what happens. You may find an easy and steady tempo.

Hammering and Picking

Fingering order and hammer order behave very much the same.

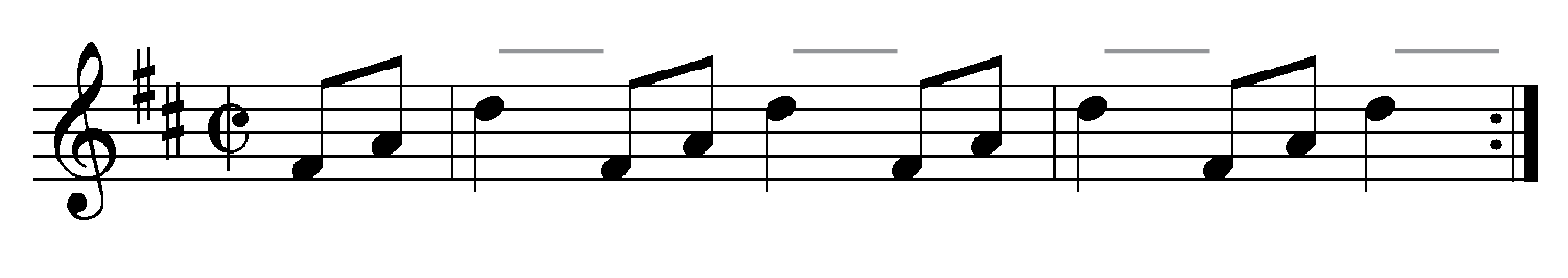

Look over this simple rhythm:

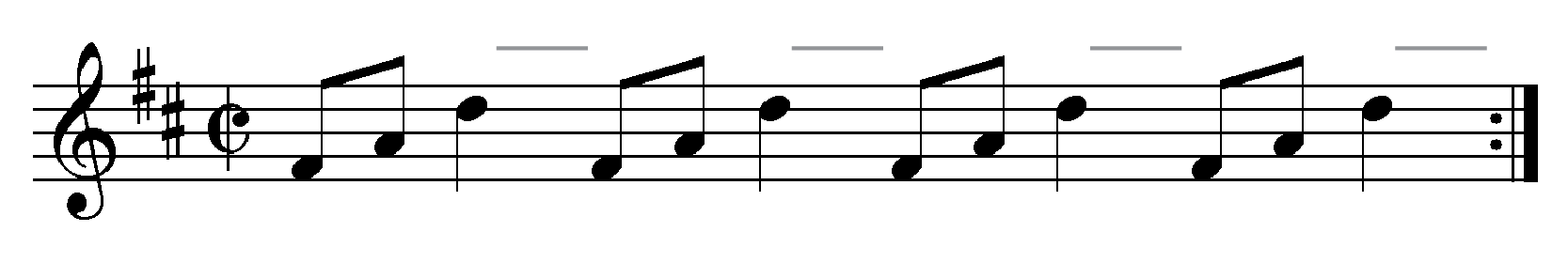

The grey lines over the staff point out the time spaces following the longer notes and assist readability. Time spaces divide the example into a series of three-note groups. Two groups include a bar line, which is fine. But let me remove the bar lines so that you can see the groups more clearly:

Why am I telling you about time spaces? Because when they are filled with continuous movement by the playing arm(s), any tempo has a better chance of coming out rock solid.

(Autoharpists, bear with me for a moment; you may see some value in this next bit. See if you can guess what I’ll be saying about playing this example on the autoharp.)

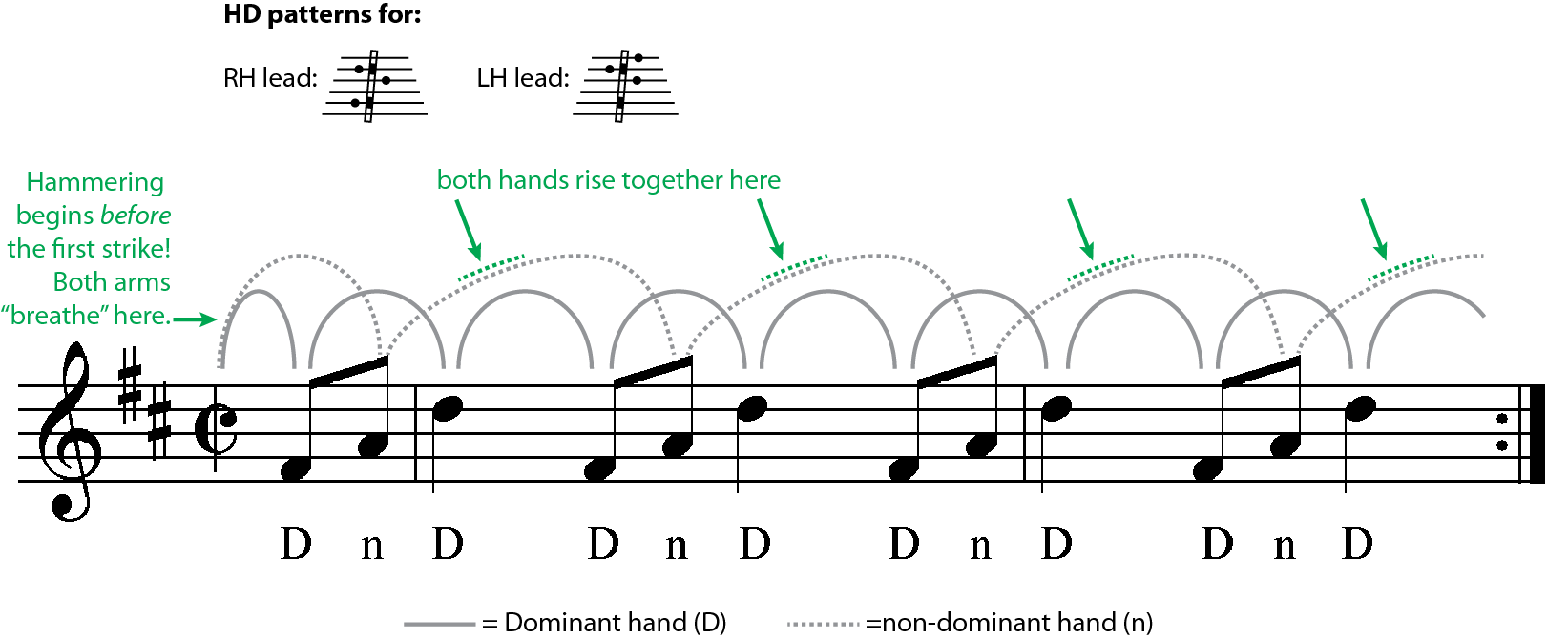

So, when playing the hammered dulcimer, I move both arms like this, with the non-dominant hand (n) rising a little higher (use the pattern suitable for your lead if you’d like to play this; as long as you follow the stroke order shown under the music, only one pattern is needed):

Notice that each three-note group always begins with the Dominant hand, allowing it to strike a steady beat on F#-D-F#-D… .

Now look at the movement of the non-dominant hand as it strikes each A. The dotted line almost looks erratic, but not so fast! This hand has more time to move, and does it by rising more slowly than the Dominant hand, ending with a quick fall to its next strike. Should the non-dominant hand fail to move continuously through the time spaces, or move partially and stop between strikes, you may be able to keep time, anyway, but it will be a struggle, or the tempo will falter. Stopping one’s hands, by the way, is inevitable when alternating strokes all the time (D-n-D—n-D-n…), so be sure to check your stroke order with what’s shown above. Also, this won’t work when flexing only the thumbs or the wrists. The entire non-dominant arm, by virtue of its length, can rise very easily over the dulcimer’s strings. You’ll get accuracy lifting the n hand from the elbow, but you’ll get magical resonance lifting from the shoulder joint.

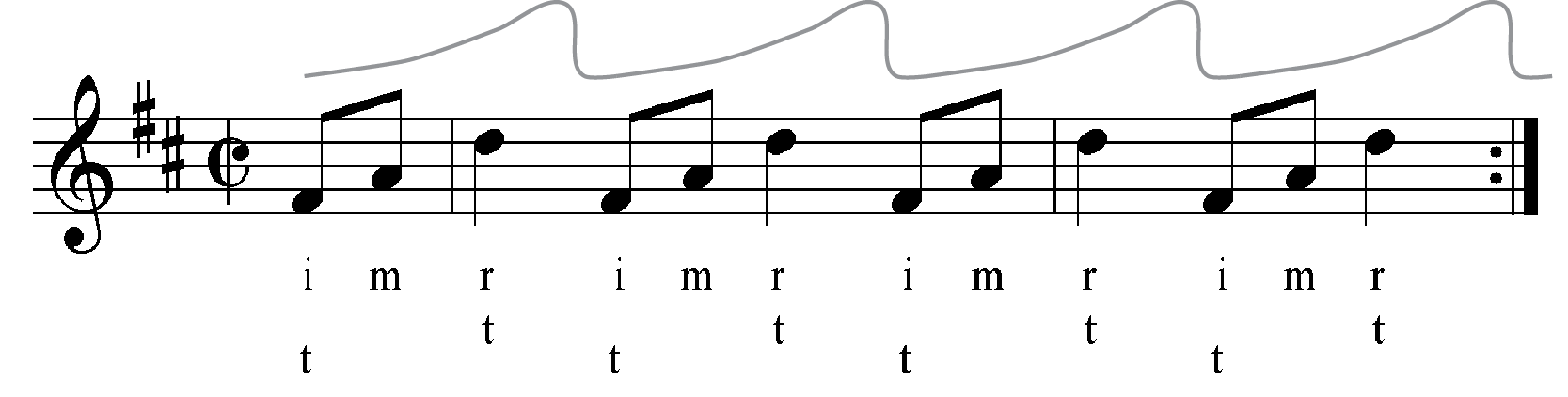

A similar thing happens when picking out the same notes on the autoharp (depress a D chord if you want to play the following OR any other major chord, striking the third of the chord first):

Assuming that the autoharp is upright against your chest when you play, notice that your hand travels a little towards the floor to play ascending pitches, and then circles back up while lifting in the time space to play the pattern again. The reverse happens when playing the pitches in descending order. So the direction of lift in any time space depends on what you’ve just played and what’s coming up next.

Notes

- Your string arm needs to be off the autoharp in order to lift in the time spaces!

- Lift the playing hand away from the strings at the peaks right over the long time spaces.

- Using the finger order shown (you’ll need three fingerpicks), you may feel a little rotation back at the elbow before lifting your string arm from way up at the shoulder joint.

Playing faster or slower

Now that I’ve introduced the basic idea for both hammered dulcimer and autoharp, to play faster, the arm(s) will lift less high. And to play more slowly, the arm(s) might lift higher, but you’ll still be able to see your hand or hammers by moving through the time space more slowly instead. This is especially true of the hammered dulcimer: lift higher and higher and pretty soon your hands and hammers leave your view and head for the ceiling, making it harder to see your way towards the next strike. You always want to have the tips of your hammers in view, even peripherally, to remain confident about your accuracy.

How to find the cause of a fluctuating tempo

- Watch yourself play in a mirror, using a side view. (Ah, I’m always thinking low-tech with a mirror because the set-up time is almost zero. If you prefer to record yourself, something hammered dulcimer players may prefer, go for it.) What kind of arm movement do you see within the longer time spaces in the rhythm? If “lift” generated by the arm(s) is missing, here is the cause of a tempo that increases speed.

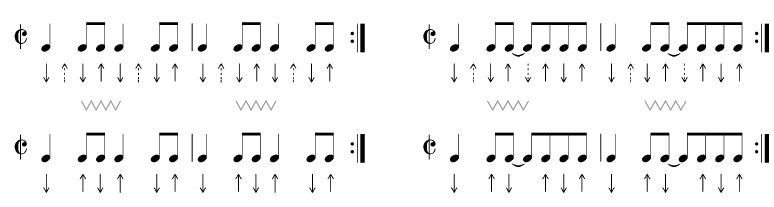

- Set your instrument aside and sing the tune to the click of a metronome (there are some great, free metronome apps on the Internet) to find out where the music is slowing down and/or speeding up. If you have struggled with metronomes in the past, doubling the number of clicks per bar will help you stay with the beat: Let’s say you want to play a tune at a metronome marking (mm) of 60, for two clicks to the bar. Double it to mm=120 to sound four clicks per bar instead:

Why didn’t my piano teacher think of this?

- If you have arranged a tune with melodic variations, sing the entire arrangement, even though it’s instrumental (obviously without harmony). Every note is suspect when it comes to tempo fluctuation. Sing the song or tune to the metronome at least twice. The first time you’ll find the fluctuations, which a second time often fixes. If not, repeat as necessary, perhaps over a couple days.

- Why does the singing slow down or speed up? When any sung rhythm subdivides less than precisely, it happens. So do more than just sing; listen to your singing to see if you can hear where the rhythm is even slightly off.

- When your singing is solid, leave the metronome going (still at four clicks per bar) and play along. Keep your ear and inner voice and ear turned on! What you heard when you sang will be helpful now as well.

Foot Tapping?

I don’t recommend foot tapping because:

- The foot is furthest from your core, where pulse and tempo need to ultimately center so that both you and the music feel grounded.

- Musical energy drains out of the foot. Stop tapping and you’ll feel all sorts of good energy go into your music-making.

- If your foot tapping is erratic (check this in a mirror), your sense of pulse is clearly compromised and will only serve to confuse your best efforts.

- Whether you stand or sit to play, foot tapping forces you to balance most to all of your body weight on the opposite foot or sitz bone. Equal weight on both feet/sitz bones is a virtue.

- Feet make noise! Sometimes this can help a tune, but more often it may not. Given the choice, I’d stay away from foot tapping as a habit so that I never have to think about eradicating the habit when it doesn’t work for the music.

Emotional Interference

Are you concerned about a big project with an impending deadline? Sad about something? Excited to be at a jam session for the first time? These and other life incidents affect tempo, especially when they remain stuck in our minds while we play. Maybe there isn’t anything you can do about it now (except the people in the jam session would probably appreciate it very much if you did). All I can offer here is to do your best to replace whatever it is on your mind with 100% of yourself in your music-making and how you move with it.

The goal

The real goal here is feeling the pulse from within, from your center. My best students are dancers who feel and enjoy(!) pulse and steady tempo throughout their bodies on a regular basis. Engage in the dance, then transfer it, not to your fingers, but to your arms and upper body. You will find simple pulse and music grounded in a solid tempo there.